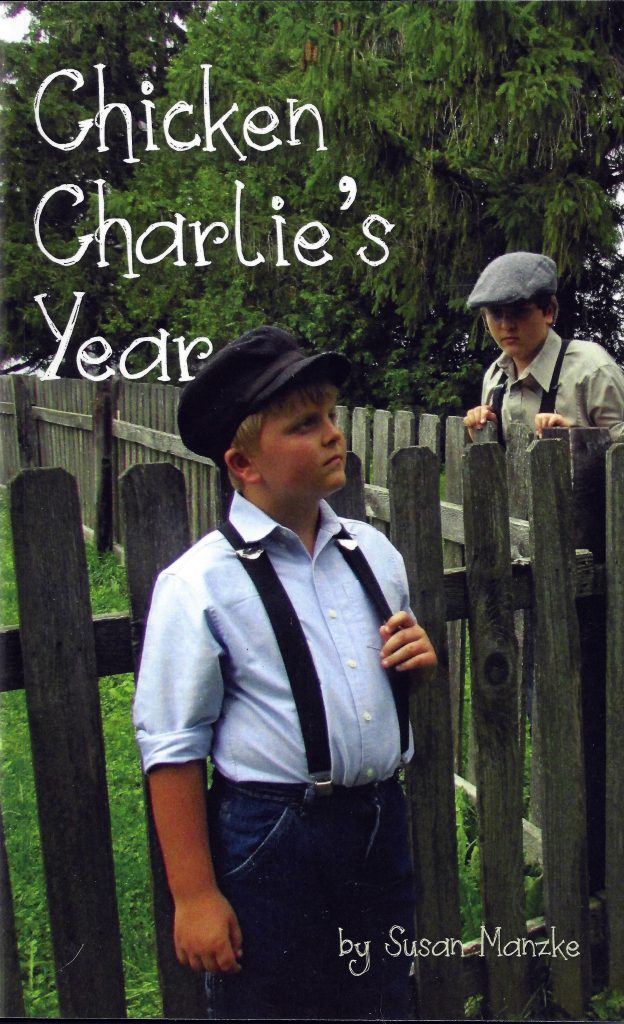

Today I’m sharing the first chapter of my novel, Chicken Charlie’s Year. It is set in the Great Depression. Each chapter is a story in itself.

Chapter 1

Christmas, 1932

Ten-year-old Charlie Petkus squirmed and dropped his pencil. All he had written was: How are you? I am fine.

His hand went to his backside, running his ragged fingernails over the wool of his long johns.

“Charlie, stop that scratching.” Bea, one of his older sisters, glared at him as she hung her apron next to the sink.

“I can’t help it,” said Charlie. He wiggled in his seat at the kitchen table. “It’s my new underwear.”

Their mother came up from the cellar carrying an overflowing laundry basket. Plop went the wash basket onto the table. “Ya, good you get long johns for Christmas,” Mama said, examining the assortment of socks and picking out those that needed mending. “You write tank-you letter to you aunt yet, Casimir?”

“I’m still thinking what to say, Mama,” said Charlie.

“You write good letter. You show what you learn in school and how smart you are, Casi, that you can write the English. I proud you know to read and write. My son, the man of house, iz learning be smart American.”

“What about Sophie and me?” asked Bea. “Aren’t we smart Americans, Mama?”

“Girls good, but Casimir is only son. With Papa long time in grave, he is man of family.” Mama sagged into a chair, settling her large frame with a sigh. “Aye-yi-yi, Casimir, you work hard at wearing out you clothes.” She held up the knickers Charlie had snagged while climbing over the neighbor’s fence.

“Sorry, Mama.” He leaned down to stroke their cat, Tigro, on the head.

“Write. Write.” She waved. “Make long letter. Tell our good news.”

“Good news?” Charlie picked up his pencil. He wiggled in his chair, but he didn’t scratch. What’s good these days, he wondered. Everyone was broke in their Calumet Park neighborhood, and in most of Chicago, too. Heck, the whole country seemed to be broke. He chewed on his pencil, and then slowly, he began to write:

Dear Aunt Mutzie,

How are you? I am fine.

Thanks for the underwear. Mama made me wear it to church on Christmas. I didn’t mean to wiggle. Those long johns are warm and itchy.

The diary is good gift, too. Mama says I have to write in it every day or I won’t get to go to the movies. She says I become smarter if I read and write. A guy doesn’t need to be so smart to work in the stockyards.

Mama’s sure 1933’s going to be better with a new president and the World’s Fair’s coming to Chicago. Some men around here are working to set it up by Lake Michigan. For us, well, Ma and Sophie have jobs cleaning and cooking for a rich family and that’s good.

So I’ll be writing in the diary every day. Wouldn’t want to miss a Saturday double feature, if I ever do get a dime to go.

Thanks again.

Your nephew,

Casimir Petkus

Charlie could barely force his hand to write his given name, Casimir. It should be a law that a kid isn’t named after a relative, he thought. So what if that relative is old and might leave them some money some day? If I ever have a kid, I’m naming him Buddy.

The only time Charlie liked the sound of his name was when his mother called him in for supper. Then it sounded pretty okay.At times like that, Casimir seemed like it had a taste to it—the taste of Ma’s fresh-made oxtail soup.

“Done.” He waved the letter in the air.

Mama looked up. “You have envelope and stamp?”

“All set,” he said. He folded the paper, slipped it into the envelope, and licked the flap. “Okay if I go mail this now?”

She nodded.

Charlie slid into his jacket and walked out the front door. He stopped at the top of the steps. No more snow had fallen since last night to mess up his sidewalk. Their yard had mounds of snow, but not a flake remained on the cement. He had shoveled before his mother had come home from work last night. “Casimir, you such good boy,” she had said and kissed him on the top of his head. Charlie smiled again as he remembered.

He tucked the letter to Aunt Mutzie into his jacket pocket and started down the street. Charlie had gone only a little way when he heard feet slapping the sidewalk behind him. He turned to see his friend Wally hurrying to catch up.

“Hey, Charlie, where you going?” Wally called.

“I’m mailing a letter to my aunt. Ma said I had to thank her for the underwear she sent, even if it itches.” He pulled at his patched britches and turned back toward the post office. Just thinking about the underwear made the wool itch all the more.

“My aunt sent me socks.” Wally pulled up his pant leg, revealing a bright red sock. “My ma says I have to be thankful for them even if they are an awful color.”

“At least no one can see what I got,” said Charlie.

“I figure if I wear them every day, they’ll wear out sooner,” said Wally. “Maybe I won’t even give them to Ma to wash. A little dirt should help wear them out faster, don’t you think?”

“I don’t think I’d want to wear this underwear for too long without washing it.” Charlie scratched his backside.

“Waldemar,” called a woman from down the block, in a long, singsong way. As Mrs. Rolenitis called again, Wally put his hands over his ears. “I didn’t hear that. You didn’t hear that. I think Ma wants me to clean out the chicken house. I told her it didn’t need to be cleaned till spring. Some of the guys are meeting by the hill to go sledding.”

“Sounds good to me, but I ain’t got no sled.”

“I bet we’ll find something thrown out in the alley.”

A horse-drawn wagon plodded down the street as the boys walked toward the alley back of Aberdeen. The driver, Moe, clicked his tongue to his horse and nodded at Charlie as he rolled past. It looked to Charlie like Moe’s horse winked at him.

Wally tugged on Charlie’s arm. “Moe gives me the creeps. He’s like a vulture circling the neighborhood, always looking for something to put in his wagon.”

“Ma says that’s how he makes money.”

“Pa says he’s a lazy good-for-nothin’,” said Wally.

Charlie shrugged. “Seems busy enough to me.”

Besides finding a wringer washer tub with a nice round bottom in the alley, the boys also found Joey and Ziggy. The brothers had tied a piece of rope to a curved sheet of metal that had once been the hood of a car. Together they were dragging it toward the sledding hill.

The washer tub went on top of the makeshift toboggan and all four boys pulled on the rope Joey had rigged up. It was a job getting all that to the top of the hill, but they didn’t care. The ride down would be worth it.

Some other guys were already sliding when they got there. Al and another kid rode flattened cardboard boxes. Shorty had his old man’s coal shovel, which left black marks in the snow as he skidded down the hill.

“Let me ride first,” said Wally. “I’ve done this before.”

Charlie agreed and helped his friend into the tub. “Ready?”

Wally had to wiggle to get his body folded just right, but soon he said, “Ready. Give her all you got.”

Charlie planted his feet and gave the tub a shove. At first, the tub didn’t want to move. Charlie had to get down on all fours and push with his shoulder. In no time, the tub slid away and down the hill. All Charlie could see of his friend was the top of his wool cap as Wally peeked over the edge.

The tub spun around, sending Wally down the hill backwards. Thump! The tub hit a bump and flipped on its side. This sent Wally rolling down the hill, and with each turn he picked up speed.

“HELP!” cried Wally.

“Hop on, Charlie,” yelled Joey from his makeshift sled. “We’ll catch up to him.”

Charlie climbed onto the car hood behind Joey, who was behind Ziggy. Sitting way at the back end made the hood seem a whole lot smaller.

All the other guys pulled on the rope or pushed on Charlie’s back to get the trio moving. After a few heaves, the car hood took off down the hill. As it picked up speed, Charlie decided it was a good thing there were no trees on this hill. This kind of sled had absolutely no steering.

Suddenly, they hit the same bump that had tipped Wally’s tub. As they flew into the air, Joey and Ziggy pushed back, sending Charlie off the back of the sled. He would have tumbled free, but a bolt on the hood caught hold of Charlie’s pants.

The thin material let loose with a rip, but Charlie’s underwear didn’t. The new wool was too strong. Instead of tearing, it pulled away from Charlie’s bottom, and that’s the way he went down the hill – on his bare behind, attached to the sled by the seat of the long johns.

“Whoa!” Charlie howled. Snow slid under his jacket and shirt, but that didn’t bother him as much as the hot snow his butt skimmed over. He knew it was frozen, but it sure felt HOT.

“Joey, stop!” Charlie yelled. He cursed in Lithuanian, which everyone understood, but Joey and Ziggy could no more stop the hood than they could stop a bullet.

Finally, they ran out of hill near Wally’s tub.

“Help me out,” called a muffled voice from inside the tub. When Joey pulled Wally free, the boy staggered to the left, then to the right. Finally Joey grabbed hold of him and Wally stood still. “I’m okay, a little dizzy, but okay.”

Charlie’s pants and bottom hadn’t done as well. His pants’ had given way and split down the back. Joey came over. “Need some help?”

Charlie shrugged away from him, pulling closed the long underwear’s back door as fast as he could, and tugging at his pants. “I’m fine,” said Charlie as he turned to face his friends. “Just caught my pants.” Cold tickled him through the rip, yet his behind felt really warm.

“You goin’ home?” asked Wally, who looked a little green.

“Not yet,” said Charlie. “But next time, someone else can sit on the back of Joey and Ziggy’s sled.” With his long johns in place, Charlie reinforced his pants by slipping a piece of rope through the belt loops. To keep the draft out, he took his jacket off and tied the sleeves around his waist. For the next hour, he joined in on many more rides down the hill, but none on the back of the hood.

Finally, Shorty offered Charlie a ride on his coal shovel. Charlie straddled it, sat on the metal shovel, and held the wooden handle with both hands. It took a bit of scooting with his feet, but soon he was swooshing down the hill. Immediately, snow started spraying up the hole in his pants. The icy stuff also managed to slip into the back flap of his long johns and chilled Charlie from the bottom up. When he skidded to a stop he was shivering.

“I better head home. My ma will be looking for me,” he said. Snow sifted down his pant leg as he turned for home.

Trying to sneak in the back door didn’t do Charlie any good. His sister Bea was coming out with a rolled-up rug and the long-handled carpet beater. Of course, she caught him. Bea always did. “Charlie, what’s the matter with you? You’re walking kind of funny.”

“Nothing’s the matter.” He tried to edge around Bea without showing his ripped pants, but Bea was too smart and spun him.

“Not another rip? Ma’s doesn’t have time for more sewing, Charlie.”

“I know.” He kicked at a chunk of snow.

“Are your new long johns okay?”

“I think so,” said Charlie.

She took his arm. “Let me see.”

“You’re crazy!” He pulled away. “They’re fine. They kept me covered okay.”

Bea stroked her chin just the way their mother did when she was thinking. “Tell you what I’m going to do. I’ll sew your pants, Charlie, and Ma will never have to know.”

“Really?” He looked up at his sister. He knew her well enough to expect a catch. “All you’ll have to do is beat these rugs for me.”

“Okay,” he quickly agreed.

“Now and every week for the next month.”

“Oh, Bea!”

“You wouldn’t want me to tell Ma, would you?”

“No,” he admitted. Charlie knew his mother had enough to think about, with money being so scarce. “You don’t have to tell Ma, Bea. I’ll do the rugs.” Maybe, he thought. He might be able to get out of beating the rugs if he had something on Bea.

“Okay. Change your pants and get to work.”

Later that night, Charlie sat down at the kitchen table and took out his blank book. Mama watched and smiled. “You man of family, Casimir. You get good schoolin’,” she said. “I like you write. You learn the English like good American.”

Charlie chewed his pencil and then wrote:

December 30, 1932

Dear Diary

Today I wrote a thank you letter to Aunt Mutzie and me and the guys went sledding. Sledding wasn’t so much fun today. Bea caught me sneaking in the back door ~~~ again.

Your friend,

Charlie

Copyright © 2020 by Susan Manzke, all rights reserved